May 12, 2013. On the way back to Earth, the astronaut Chris Hadfield (2013) released a music video of a modified rendition of Space Oddity by David Bowie previously recorded on the International Space Station – ISS. The fact that a song about an astronaut was sung on a real space station triggers an unsettling sense of dizziness which induces to reflect on the relationship between realism and (science-)fiction.

If in 1969 Space Oddity could be interpreted as a metaphor of the existential condition of the modern man, its cover of 2013 – with subtle text modifications – assumes the character of an intimate narration of a veritable lived experience. The different scenery between the original music video and the version of Hadfield are emblematic for understanding that gap.

The first one, starring David Bowie, resumes – although strongly stylized – the canons of the science fiction imaginary so popular at the end of the 1960s – silver space-suit, white walls and blinking lights. On the contrary, in the second video everything is real: the bulkheads and the equipment in the background are true, as well as the planet Earth seen beyond the portholes of the space station.

This example is essential because it reveals the complex relationship between an old representation of the future and the present age. The aim of science fiction – contrary to what is often asserted by a superficial commonplace – is not the prediction of the future, but the expression of the present time through the representation of a probable future. In this context, the point of contact between the present and a past representation of the future is a rare but extremely significant event.

It will probably take a long time before an entire film can actually be filmed in space, therefore directors and set designers will be able to pursue their work by imagining human habitats outside the atmosphere even in the decades to come. However, in recent years a return of the concept of verisimilitude in science fiction cinema is arising. A sort of sci-fi neorealism spreading nowadays invites us to focus the different ways in which the future was conceived during the last 120 years, since the first release of a film about space flights.

The adventure film Le Voyage dans la Lune by Georges Méliès, one of the first and most popular film of cinema since its beginning – the scene of the bullet-capsule landing in the Moon’s eye is one of the most iconic images in the history of cinema – was focused on a satirical intent rather than on the will to represent a credible future. From this point of view the story narrated by the film is closer to the prodigious journey of paladin Astolfo on the Moon (Ariosto 1516, 70-87) than the description of a modern space flight. Nevertheless, it is generally considered to be the first science fiction film.

However, the first film that tries to create a realistic setting for a story based on space flights is probably Woman in the Moon – Frau im Mond – directed by Fritz Lang. The film makes use of the renowed scientist Hermann Oberth’s advice and credibly represents, for the first time, the use of a rocket to bring a crew to our satellite. In this case the use of a few openable maquettes are a typical way to represent the complex structure of such a futuristic vehicle. Some inventions are particularly ingenious, like the double color – light-dark – of the rocket to manage the heating of the vehicle by orienting one of the two sides towards the sun. In this film there is one of the first scenes of aestheticization of a spatial landscape: during the space flight the astronauts flock to one of the windows to observe the sun rising from behind our planet, which still today is represented in a credible and fascinating way.

On the contrary, some narrative expedients seem quite naive, such as the invention of spreading on the surface of the spaceship’s cabin with handles, both for hands and feet, in order to support the movements of astronauts in the absence of gravity. In the film the diver suits are useful to face the lunar soil before discovering that, in the cinematic fiction, our satellite has a breathable atmosphere. The film is divided into two parts, and the scientific accuracy in the reconstructions of the spacecraft contrasts with the representation of the crew more similar to explorers or adventurers rather than credible astronauts.

If the scenography of Frau im Mond is interesting for the attempt to reconstruct in a plausible way the technical aspects of a space flight, it will be a 1936 Soviet film, Kosmičeskij rejs, providing viewers with a broader representation of the future. The film, set in 1946, presents scenes which directly recall Constructivist Architecture. Not only there is an attempt to represent a space journey, but the staging of a future in which the construction of a spaceship is made possible by the power and efficiency of an entire economic and industrial system. In the film also there is an accurate and fascinating description of the movements of astronauts in zero gravity, allowed by the large dimensions of the spacecraft. The vehicle, anticipating several and more recent representations of spaceships resembles more to a large airship – with a clear reference to the age of Zeppelins – than to a credible space rocket.

World War II momentarily puts an end to the interest in the film focusing on space travels or science fiction in general, but in the post-war period, and in the political context of the Cold War, there is a revival of these topics, albeit with profound differences both from a technical and a social point of view. In the Western science fiction films of the 1950s and early 1960s the imagery of space flights is closely related to the scenographic representation of war films and integrated within the fears of the Cold War.

Flight to Mars is a film staging a plot that has some points of contact with the Soviet film Aelita, although with a greater attention to the topic of space flights and a quite conventional setting: the references to historical avant-gardes are replaced with the imagery of comics and popular literature. The model of space traveler is aligned to that of the soldier and – beyond a slight veneer of science fiction – the interior of the spacecraft with its machinery very closely recalls the image of a battleship of World War II.

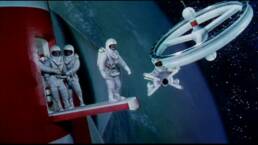

The reference to war films is even more direct in Conquest of Space; the film intends to be a plausible representation of the future by including the representation of a large orbital wheel-shaped base. Life in the space station is strictly built on the model of an American military base. Overall, the film moves on two levels that today seem quite distant from each other. On the one hand there is a series of space adventures attentive to the verisimilitude of the sets. Both the vehicle and the space base are reconstructed on aeronautical models; astronaut suits are moving away from the original diver’s underwater model. The position occupied by the astronauts in the spacecraft follows with good reliability the one of the first space flights, while ingenious mechanical solutions – such as a retractable ladder coming out from the side of the rocket – appear. On the other side, beyond the scenography, the film presents strong analogies with the popular war cinema, incorporating some references to the almost contemporary The Caine Mutiny.

The model of the military ship is also present in the masterpiece of the American space science fiction of the 1950s, Forbidden Planet. In this case the topic of space flights is only marginally developed in a script which is remotely but intelligently inspired by The Tempest by William Shakespeare, with a priority to the mystery and psychological aspects of characters.

An exception to this rule is Destination Moon, a film which intends to reconstruct a mission to the Moon with maximum scientific reliability. In the film, scientists, soldiers and businessmen come together in a common effort to give their nation the primacy over space flights. During the narration – a case of films inside the film – the protagonists attend the screening of a cartoon starred by the popular character Woody Woodpecker: this expedient has been used to allow the understanding of complex technical topics also to a public of children.

From the early 1960s – and to be precise as the first flight in the space of Jurij Gagarin of 12 April 1961 takes place – the comparison between science fiction cinema and real space missions begins. Between the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s the cinematographic representation of space flights in the Soviet Union also has the function of celebrating technological achievements in the socialist countries. Nebo Zovyot and Planeta Bur are space adventures showing a possible future of space flights; their scenographies, although remaining clearly futuristic, try to maintain a certain level of verisimilitude.

Mechte navstrechu, while departing from the representation of a near future, has the merit of providing some extraordinarily suggestive images about the city of the future. In Tumannost Andromedy, set in a rather remote future, the spaceship loses all reference to the usual shape of the rocket to become a large structure in which furniture and machinery is arranged in large spaces apparently surrounded by mega screens that cancel its boundaries. A powerful photography and a suggestive use of the depth of field effect make the scenes particularly effective.

The 1960s represent a golden age for science fiction cinema which, ultimately, contains the seeds of the decline of this film genre. In the same years architectural culture began to take a serious interest in the contacts and contaminations between the spatial imagery and the ways of life of human beings on Earth. The author who has investigated more consistently these arguments is certainly the British critic and architectural historian Rayner Banham. Presumably, one of the most effective summaries of these topics can be found in an article (Banham 1968) entitled Triumph of Software and published for the first time in the magazine New Society in 1968. The article talks about two science fiction films released in the same year: 2001. A Space Odyssey – release date April 1968 – and Barbarella – release date October 1968. Banham interprets the release of Barbarella, only a few months after Kubrick’s 2001, as the significant sign of a change in the way we conceive relationships between mechanical and architectural elements. The nonconformist spirit of Banham leads him to support the greater adherence to the spirit of the time of the Vadim film compared to Kubrik’s masterpiece.

In 1977 Banham will return to deal with cinema and popular culture by dedicating an article, entitled Summa Galactica, to Star Wars, a film which is considered emblematic in representing the progressive transition from science fiction to “space opera.” In a period in which the fascination of the space race was decreasing the film industry did not intend to abandon this topic, but wanted to decline it into new, more popular, film genres.

On the contrary, Capricorn One stages a government plot to cover up the failure of a Mars mission. The representation of space technologies seems to be the simple revival of the Apollo mission’s aesthetic, but, on the other hand, space travel is only a pretext for a story centered on the lies of politicians and the search for truth.

Since the 1980s, a new film genre that could be defined as historical-astronautical arises. Films such as The Right Stuff and Apollo 13 tell the stories of past events which occurred at the time of the space race. At the end of the twentieth century, science fiction as a main cinematographic genre was partly replaced by fantasy, space opera and cyberpunk. Spatial science fiction, and its need for verisimilitude, seem to have finally disappeared along with the modernist confidence in the future. The fantastic scenarios of the space opera and the urban and social dystopias seemed more suitable to give shape to the anxieties for the near future.

However, as the historical space-travel genre emerged since the 1980s, a new phenomenon is currently arising. It could be considered as a new expression of “science fiction neorealism.” The spatial imaginary is returning – with movies like Moon or Europa Report – not as a repertoire of futuristic forms, but as a synthesis of realism and retrofuture. The references to 1960s aesthetic merge with images that seem to come straight from the real living and working habitat of astronauts.

In particular, the setting of Europa Report is directly inspired by the interiors of the International Space Station. In Moon, the theme of the alienation of a spaceman returns to be the central element of the narration, just as in the song Space Oddity. It is interesting to point out that the movie is directed by Duncan Jones, the son of David Bowie.

Therefore, it is possible to argue that the twentieth century movies were mainly focused on challenge and exploration, while the neorealism science fiction of the twenty-first century is focused on the isolation of the astronaut or on the peculiarity of community life inside the spaceship. Space thus becomes the symbolic place representing the contemporary human condition after the loss of faith in the grand narratives and the decline of the post-modern ironic view of life.

Reference List (book)

- Ariosto, Ludovico. Published for the first time in 1516. Orlando furioso, XXXIV.

- Banham, Reyner. 1968. “Triumph of Software.” In Design By Choice, edited by Penny Sparke, 133-136. 1981. London: Academy Editions. (Previously published in New Society, 31 October 1968).

- Banham, Reyner. 1977. “Summa Galactica.” In Design by Choice, edited by Penny Sparke, 137-140. 1981. London: Academy Editions. (Previously published in New Society, 27 October 27).

- Hadfield, Chris. 2013. An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth: What Going to Space Taught Me About Ingenuity, Determination, and Being Prepared for Anything. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Reference List (video)

- Le Voyage dans la Lune. Directed by Georges Méliès. 1902 [Motion Picture].

- Frau im Mond. Directed by Fritz Lang. Screenplay by Fritz Lang. Thea von Harbou. 1929. [Motion Picture].

- Космический рейс [Kosmičeskij rejs: Fantasticheskaya novella]. Directed by Vasili Zhuravlov. 1935-36 [Motion Picture].

- Flight to Mars. Directed by Lesley Selander. 1951 [Motion Picture].

- Аэли́та [Aelita: Queen of Mars]. Directed by Yakov Protazanov. 1924 [Motion Picture].

- Conquest of Space. Directed by Byron Haskin. 1955 [Motion Picture].

- The Caine Mutiny. Directed by Edward Dmytryk. 1954 [Motion Picture].

- Forbidden Planet. Directed by Fred M. Wilcox. 1956 [Motion Picture].

- Destination Moon. Directed by Irving Pichel. 1950 [Motion Picture].

- Небо зовё [Nebo Zovyot]. Directed by Valery Fokin. 1959 [Motion Picture].

- Планета Бурь [Planeta Bur]. Directed by Pavel Klushantsev. 1962 [Motion Picture].

- Мечте навстречу [Mechte navstrechu]. Directed by Michail Karjukow, Otar Koberidse. 1963 [Motion Picture].

- Туманность Андромеды [Tumannost Andromedy]. Directed by Yevgeni Sherstobitov. 1967 [Motion Picture].

- 2001: A Space Odyssey. Directed by Stanley Kubrick. 1968 [Motion Picture].

- Barbarella. Directed by Roger Vadim. 1968 [Motion Picture].

- Space Oddity. Written and performed by David Bowie. (First released as a 7-inch single on 11 July 1969). [Music Video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRMZ_5WYmCg.

- Capricorn One. Directed by Peter Hyams. 1978 [Motion Picture].

- The Right Stuff. Directed by Philip Kaufman. 1983 [Motion Picture].

- Apollo 13. Directed by Ron Howard. 1995. [Motion Picture]

- Moon. Directed by Duncan Jones. 2009 [Motion Picture].

- Space Oddity. Written by David Bowie and performed by Chris Hadfield. [Music Video] htps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KaOC9danxNo. (Also in Space Sessions: Songs from a Tin Can. Chris Hadfield. 2015 [Album])

- Europa Report. Directed by Sebastián Cordero. 2013 [Motion Picture].

Gian Luca Porcile

Ph.D. in Architecture. His main research interests are architectural theory and urban studies. He teaches History of Architecture at Department of Architecture and Design (dAD), University of Genoa.

Paola Sabbion

Ph.D. in Architecture, has been teaching and researching at dAD, University of Genoa, since 2009. She is author of papers, essays, and monographs, focusing on history and theory of landscape.