Fondazione Maxxi. Superstudio, Atti Fondamentali. Educazione. Progetto 1, 1971, Litografia

Today’s Italian academic education system lives in a state of continuous stasis, studded by areas of penumbra, alternating with situations of international excellence.

This is due to various implications, like Governances, both from the more political-institutional side and from the operational practical side, which many times have not been adequate to the position they were going to hold, then again the commodification and corporatization of a public cultural institution, which led to having to report the result of an intellectual process, in which, however, as Maurizio Bartolini (IlSole24Ore) says, research funding and public funds halved rather than duplicated.

The feudalization of areas and lines of research on bibliometry and scientometry criteria, supported by acronyms of difficult definition and coded strings by an immeasurable bureaucrat, which make precarious university careers, devastating the cultural, social and economic system not only of the academic dimension but of the entire Italian system.

Altro che senza futuro, siamo senza presente!

— IL RE TARANTOLA, Non ho mai avuto il fisico di una volta II

The Federazione Lavoratori della Conoscenza (FLC) notes that “the university stands for a significant part of its precarious work activities, a condition that affects one worker out of two of the research and teaching staff. This status of permanent staff is penalized and in many universities there are no funds to recognize and enhance the work done. It’s certainly no more rosy regarding the right to study, starting from the level of university fees and the small minority of enrolled students who benefit from a scholarship, ending up with the structural shortage of residences and beds.”

This situation is the progress of a process that began on 30 December 2010, the end of which is not seen and which in reality is simply the mirror of a widespread condition at different levels in different dimensions of the Italian society, but the connection and referring to similar times, where the game of the barony and elitism in Italian universities prevailed, it is with the ’68 and the student movement where the increase in the cultural level and the maturation of society allowed middle and university students to ask for reforms and to obtain greater participation in decisions concerning academic activities.

Transcending the controversies that led to that movement, for example Pasolini attacked this movement for the famous clashes of Valle Giulia:

[…] Adesso i giornalisti di tutto il mondo (compresi

quelli delle televisioni)

vi leccano (come ancora si dice nel linguaggio

goliardico) il culo. Io no, cari.

Avete facce di figli di papà.

Vi odio come odio i vostri papà.

Buona razza non mente.

Avete lo stesso occhio cattivo.

Siete pavidi, incerti, disperati

(benissimo!) ma sapete anche come essere

prepotenti, ricattatori, sicuri e sfacciati:

prerogative piccolo-borghesi, cari.

Quando ieri a Valle Giulia avete fatto a botte

coi poliziotti,

io simpatizzavo coi poliziotti.

Perché i poliziotti sono figli di poveri. […]— Pier Paolo Pasolini. Il Pci ai giovani

Initiatives of rupture and pro-sixty-eight made their way as well into the sphere of the project.

The stalemate in which the Italian academic system is located is analogous to the condition of suspension experienced by society and culture in the aftermath of the end of the Second World War, with a new order that had not met the hopes for change that, for everyone, should have occurred in the aftermath of the conflict resolution. A new beginning that never really happened, which provoked the explosion of the protests of the second half of the 1960s. The story of Apollo 11 is part of this parallel on the one hand as a term of the context, representing a decidedly establishment initiative, on the other hand it has embodied, somewhat curiously, a symbol of revival, of new hope, also in the context of those protests and recriminations. Like many other key events scattered a bit in all fields, as a sign that the kind of discontent and the kind of challenges that we saw projected into the future actually involved everyone, as part of a single collective wisdom.

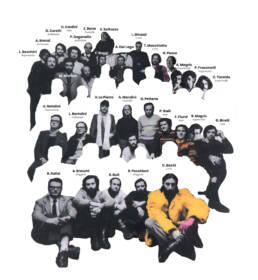

In 1973, when the experience of radical design – celebrated one year before in the exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape at MoMA, New York – was exhausted, the protagonists of that movement decided to give life to a series of proposals. and education-related experiments under the name of Global Tools.

Global Tools can be considered an authentic revolution that started from the uprisings of ’68 when it was said: «We need to get out of universities, from school and draw on the original source of culture, ideas, of what spontaneously comes out of the most unexpected places of society”. This goes beyond any specialized competence that remains a value but not exclusive and dominant.

—Riccardo Dalisi. Riflessioni sulla Global Tools

While in those years the specter of an impossible proletarian revolution and then that of terrorism began to become agitated in Italy, for some time now the combination of political consciousness and avant-garde vocation have seen the birth of groups that contest the project as it was until then conceived.

In Florence with Archizoom, UFO, Superstudio and Gianni Pettena, in Milan with Gaetano Pesce, Alessandro Mendini, Ugo La Pietra, Ettore Sottsass, in Naples with Riccardo Dalisi, a radical revision of the rationalist and functionalist conventions comes to life, seeking and experiencing an attempt to emerge and subvert the panorama of uncertainties of the period with a counter-trend design, a criticism of modernism and often also a protest against the models and institutions of that time.

Institutional teaching, considered in the historical impossibility of finding new valid criteria for the future. The school is not made of beautiful or ugly school buildings. It does not apply at fixed times … Ultimately the school consists in living instead that in learning.

—Alessandro Mendini. Un uomo è una scuola

This programmatic experience, which took place between Milan and Florence, of experimental didactic workshops, among peers, was organized on the basis of the relationships between the various working groups, hinging the debate on broad topics such as construction, body, communication, theory and survival. The approach was the one aimed at the propagation and diffusion of the use of natural materials and techniques and related to sharing and contamination behaviors, through a collective project in continuous transformation, to make the experience transmissible and multiplicable, leaving developments open and therefore defining an alternative to traditional education with the aim of designing a new model of life as permanent global education.

We could define this movement, albeit extemporaneous, as the “project hackers,” or at least as an intent to oppose the old establishment of architecture and design, from which they were opposed because in them it saw a form of dangerous criticism of the system, just like the contemporary overseas hacker movement, for which the transmission and diffusion of knowledge had to take place in a free and shared way. Himanen (2001, 65) compares the Platonic academic learning model to that of the hacker community: “the free individual must not be forced, like a slave, to learn any discipline – it is totally different from that of the monastery (and of the school), in which spirit is represented by Benedict’s monastic rule: ‘It is up to the teacher to speak and teach, keeping silent and listening befits the disciple.’”

The Greek academy represents the open source mentality, which allows an open creative and generative process, which self-corrects thanks to the contribution of the community. Fifty years after the global tools, in Italy there are different realities of this type, whose values and concepts of collective innovation and shared experimentation, of counterculture and aversion to the system contaminate the world of design; and perhaps one of the best and most well-structured forms of homage to Global tools can be found in the laboratories and initiatives of the Scuola Open Source9, a community of digital artisans, makers, artists, designers, programmers, pirates, planners and innovators who deal with research for the public and the private sector, teaching for children, adults, the unemployed, professionals, pensioners or managers, developing products, services, technology and human capital, through social and technological innovation projects.

Note to the text

Original version of the text by A. Mendini: “La didattica istituzionale, considerata nella impossibilità storica di reperire nuovi criteri validi per il futuro. La scuola non è fatta di edifici scolastici belli o brutti. Non si applica a orario fisso… In definitiva la scuola consiste nel vivere invece che nell’imparare”.

English version of Pasolini’s poetry excerpt:

[…] Now journalists from all over the world (including

those of televisions)

they lick you (as they still say in language

goliardic) ass. I don’t, dear.

You have faces of dad’s children.

I hate you the way I hate your dads.

Good breed doesn’t lie.

You have the same bad eye.

You are fearful, uncertain, desperate

(very well!) but you also know how to be

bullies, blackmailers, safe and brazen:

petty-bourgeois prerogatives, dear.

When yesterday in Valle Giulia you got into a fight

with the cops,

I sympathized with the cops.

Because the cops are children of the poor. […]

Reference list

Bartoloni, Maurizio. “Università senza cervelli: in 10 anni dimezzati i giovani ricercatori,” IlSole24Ore (9 May 2019). https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/in-10-anni-dimezzati-giovani-ricercatori-e-90percento-sara-espulso-atenei-ACodjh

Borgonuovo, Valerio, and Franceschini, Silvia. 2018. Global tools: Quando l’educazione coinciderà con la vita, 1973-1975. Rome: Nero editions.

Dalisi, Riccardo. “Riflessioni sulla Global Tools,” Archimagazine (5 September 2018). http://www.archimagazine.com/riflessioni-sulla-global-tools.php

De Luna, Giovanni. “La verità della storia: Pasolini e gli scontri di Valle Giulia del ’68,” Centro Studi Pier Paolo Pasolini Casarsa della Delizia (2 March 2018). http://www.centrostudipierpaolopasolinicasarsa.it/molteniblog/la-verita-della-storia-pasolini-e-gli-scontri-di-valle-giulia-del-68-di-giovanni-de-luna/

FLC CGIL. “Università in piazza il 9 gennaio” (4 January 2020). http://www.flcgil.it/universita/universita-piazza-9-gennaio.flc

Himanen, Pekka. 2001. The Hacker Ethic and the Spirit of the Information Age. London: Vintage.

Il re tarantola. Non ho mai avuto il fisico di una volta II. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SpjMp4pcEV4&feature=youtu.be

Pasolini, Pier Paolo. “Il Pci ai giovani,” L’Espresso (16 giugno 1968)

Petroni, Marco. “Fabulations. Global Tools, la rivoluzione della non scuola,” Artribute (12 Febraury 2019). https://www.artribune.com/editoria/libri/2019/02/global-tools-silvia-franceschini-valerio-borgonuovo/

Scuola Open Source. http://www.lascuolaopensource.xyz/

Zunino, Corrado. “Università, il Tar contro la legge Gelmini,” La Repubblica (8 April 2019). https://www.repubblica.it/scuola/2019/04/08/news/universita_il_tar_contro_la_legge_gelmini_crea_precari_a_vita_-223537018/?refresh_ce

Xavier Ferrari Tumay

A designer without a black and white profile picture.

On Instagram: @xavierferraritumay